Homo Ferus

Ash Tree Wife

In Hamrånge grew the largest ash I ever beheld in these latitudes. It stood on the outskirts of the parish, surrounded by dilapidated dwellings. I wondered why no man, woman, or child would look at it, or go anywhere near its roots. It took me much of the day to learn the answer: the Ash Tree Wife.

Carl Linnaeus, May 16th, 1732

Banshee

Glenblane House is by no means the only house in Scotland with a family tradition of a banshee. Mr. Duncan Glenblane, the current laird, told me her story over a glass of the excellent local whisky. During the wars of the Covenant, the house was sacked and all its occupants slaughtered, save one servant woman who jumped to her death from the high tower rather than submit herself to murder and worse. The screams of her tortured spirit are a sure and baleful omen for the family, and the laird assured me that he had heard her on the night of his own father’s death.

William Stukeley, April 1721

Black Dog

Finding myself overtaken by darkness on the road ’twixt Taunton and Bridgewater, I was surprised, and not a little anxious, to find a large black dog padding silently beside my horse. I dared not speak, and the dark, shaggy beast, whose size I estimated to be that of a yearling calf, did not favor me with a glance or any other sign. Passing a crossroads a little way from my destination, I looked down to find that my companion was no longer there, though I did not see it leave the road. I learned later that the creature was well-known in the district, and rarely did harm.

William Stukeley, October 1710

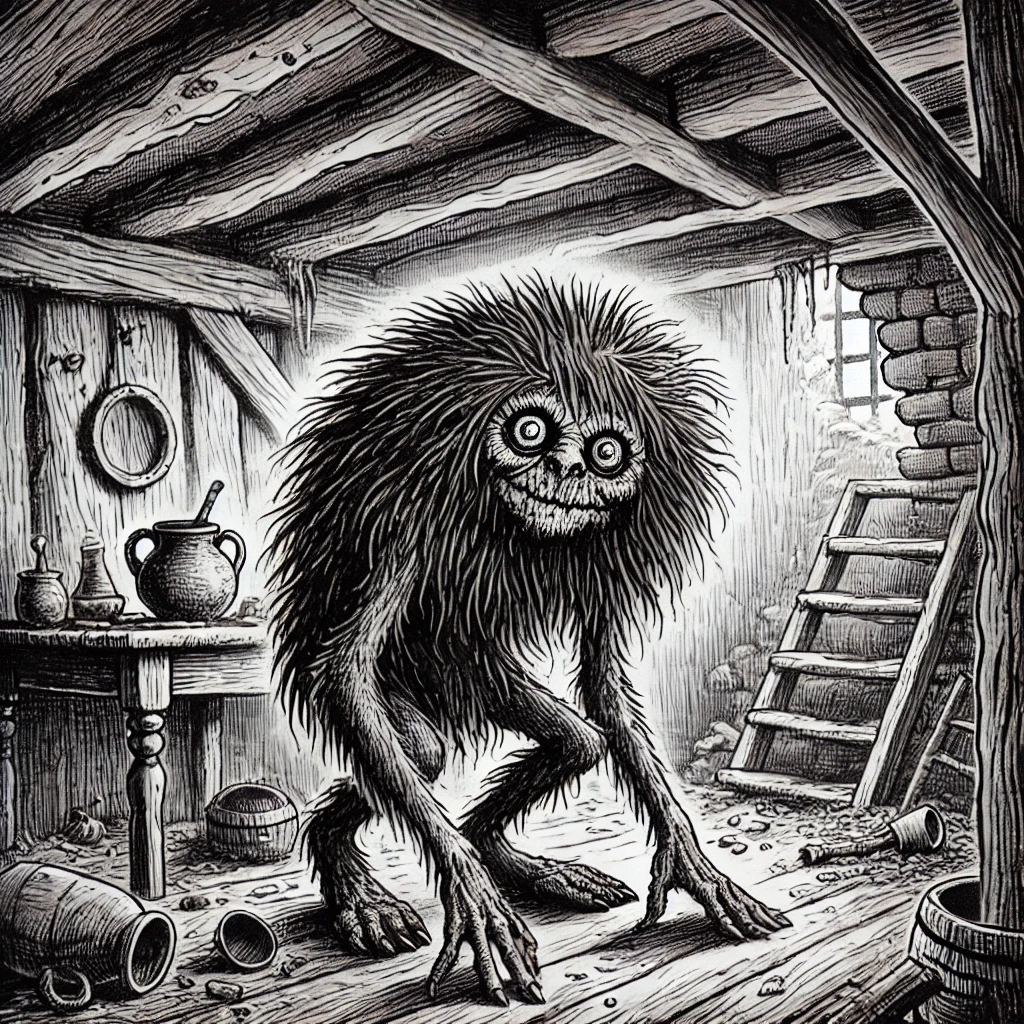

Boggart

The area was abuzz with news of a local farmer whose farm was haunted by a troublesome spirit called a boggart. As well as causing all manner of mischief around the house, the creature denied its hosts a wink of sleep, keeping them up all night with ear-splitting crashes and screams. The local parson, arriving with bell, book, and candle to exorcise the spirit, had been sent packing with a bent candlestick and his hat aflame, and the proper ways to deal with such an infestation were the sole topic of conversation in ever hostelry for several miles around.

William Stukeley, July 1721

Brook Horse

Never had I thought I would be swimming in a murky pond after the stroke of midnight. But here I am, far away from tonight's supper with Mr. and Mrs. Ångström up at the Academy. A white stallion in the splendor of the moonlight, standing among the lily pads on the bank of the Fyris River. A foolish wager made on the canal. Suddenly I found myself on a nightmarish ride away from Upsala Cathedral, through Sala Municipality, past the estates of Avesta and the kilns of Kullhyttan, clinging to the wet back of the brook horse. Good golly, what a sobering up. Now it seems I am left in the wild, with only a mocking neigh as evidence…

Carl Linnaeus, May 3rd 1732

Church Grim

We have arrived in Lycksele after traveling up the Ume River. Many falls threatened to capsize our vessel, and we suffered heavy rain and swarms of mosquitoes that drove me to the brink of madness. The villagers are remarkably taciturn. A woman claimed the village was cursed and the water full of tadpoles. Apparently, she had to drink hard spirits not to belch up frogs. I inquired about the source of this black magic. She pointed at the rickety woodden church on the edge of the village, saying that the handsome pastor from the south is punishing the people of Lycksele for not taking him into their hearts. I went to see him. Reverend Gran was indeed an elegant young man. He stood in the doorway with darkness behind him and asked me whether I thought it possible to make decent people out of these wayward locals. When I mentioned the supposed curse, he immediately turned gruff. Something stepped out of the darkness. The largest dog I have ever seen rubbed its head against the pastor's leg, glaring at me with its red eyes. I realized that the beast was not of this world. Perhaps I really did go mad from those infernal mosquitoes keeping me awake for days on end.

Carl Linnaeus, May 30th, 1732

Dullahan

The road between the town and the graveyard is shunned by the locals, for fear of a headless rider who is said to collect the souls of the doomed on behalf of “Crom Dubh”, which as far as I was able to discover is an ancient spirit of death. No one escapes this relentless hunter of souls, I was told, but despite that I met one man, venerable but still hale, who claimed to have survived an encounter thanks to a gold coin that he wore around his neck on a leather thong.

William Stukeley, October 1712

Fairy

I lie shivering in bed next to my fellow travelers. They scream as they are plagued by nightmares. Our skin is blemished with blisters, and our lips swollen like strawberries. The malady struck us halfway to Sorsele. That night I dreamed that I was awake. I rose from my bed in the light of luminous little creatures that flew between trees and rocks. They giggled and mocked me in ways that ought not to be transcribed. Somehow I felt compelled to follow them on a path I had not noticed during the day. We arrived at a bright green lake, so vast that I could not see the shore on the other side. From the deep arose a creature that, for lack of better words, resembled a whale. It opened its jaws to reveal a mouth filled with gleaming treasures. The winged creatures prodded me to step inside and help myself to its riches. When I hesitated, they reviled me in the foulest terms. Something made me turn around and head back. This infuriated them. One of the creatures flew to my face and blew some form of dust which made me cough. Shortly thereafter I woke from my slumber, and we were all very ill.

Carl Linnaeus, June 3rd, 1732

Ghost

At Kronoby Hospital I sat with numerous maniacs whose minds had been broken by misfortune or liquor. Their ramblings made little sense, as one would expect, yet there was a consensus that a man named Elias Gren, a patient who hung himself in the hospital attic, wandered the corridors waiting for his wife and children, who never visited him after his descent into lunacy. They snuck me past the treatment rooms and pointed at the attic stairs which Elias had climbed to meet his doom. There was a light glowing from the attic, blue and most unnatural. But I hesitated, and when I finally mustered the courage to go up there the attic was dark, empty, and smelling of dust.

Carl Linnaeus, September 20th, 1732

Giants

A farmer named Otto Person at the Grimsmark Inn spoke of a mountain where he had found large quantities of copper. When a man from the Board of Mines in Umeå was sent to investigate the matter, he found nothing but gray rock. Otto contended that the giants, who had lived there since before mankind, were hiding the riches of the mountain.

Carl Linnaeus, June 13th, 1732

Glaistig

Glenfuath – the vale of the frightful spirit, in the Gaelic – was well-named, as I discovered. Beside the ford at Hagburn I saw by the roadside a young and attractive woman dressed in green, who reached up imploringly and gave me to understand by her gestures, for she spoke no English and I none of the Scottish tongue, that she desired me to let her mount behind me and carry her over the ford. Having been forewarned by local tradition, though, I resisted the chivalrous instinct and left her where she sat, and by so doing, I was told, most likely saved my own life.

William Stukeley, August 1714

Hag

The standing stones of ancient times are the subject of many tales told among the rural folk who live nearby. While travelling across the county of Gloucester I came upon a typical example in the tale of Old Meg. The gray and weathered stone, not quite the height of a man and a little broader, stands on a valley side near the village of Annonsbury, and is held by the local people to be the body of a pagan witch, who was turned to stone through the prayers of Saint Birinus during his mission of conversion in these parts.

William Stukeley, June 1724

Knocker

I had returned to my lodgings after a day spent surveying the ancient tin workings, some of which date from Biblical times, when a fellow drinker jokingly asked me if I had encountered any of the Knockers. A hush immediately descended upon the tap-room, and others present, locals all, assured the speaker that the little people of the mines were not to be spoken of lightly, lest some disaster befall the mine and the community it supported. Ruffled spirits were only soothed by a round of drinks for the house.

William Stukeley, May 1716

Leprechaun

That morning one of my host’s tenants begged the favour of an audience, and I heard afterward that he had come into enough money to buy out his lease and take ownership of his cottage and its land as a freeholder. The locals were at a loss to account for his sudden prosperity. Some muttered that the coin was somehow ill-gotten, though never in the man’s hearing. Others, older or after an evening’s drinking, whispered that he had got the better of a leprechaun, although they were careful to avoid naming the creature, using the formula “the little shoemaker” to evade the wrath of the fairy folk.

William Stukeley, September 1712

Lindworm

We had to travel down the river again, but alas we brushed against an islet. The boat broke. My companion lost his boat, his axe, and a pike – I lost a couple of stuffed birds, including a heron. After wringing the water out of our clothes and walking a mile along the shore, we came upon a settler who gave us food. His name was Oscar. His face was pockmarked with disease, although he ascribed it to the acid spit of a rolling whiteworm. I assumed the illness had ravaged his mind. When we left, I saw something huge slither through the woodds. I asked my companion what the monstrous creature could be, but he saw nothing but trees and shrubbery.

Carl Linnaeus, June 4th, 1732

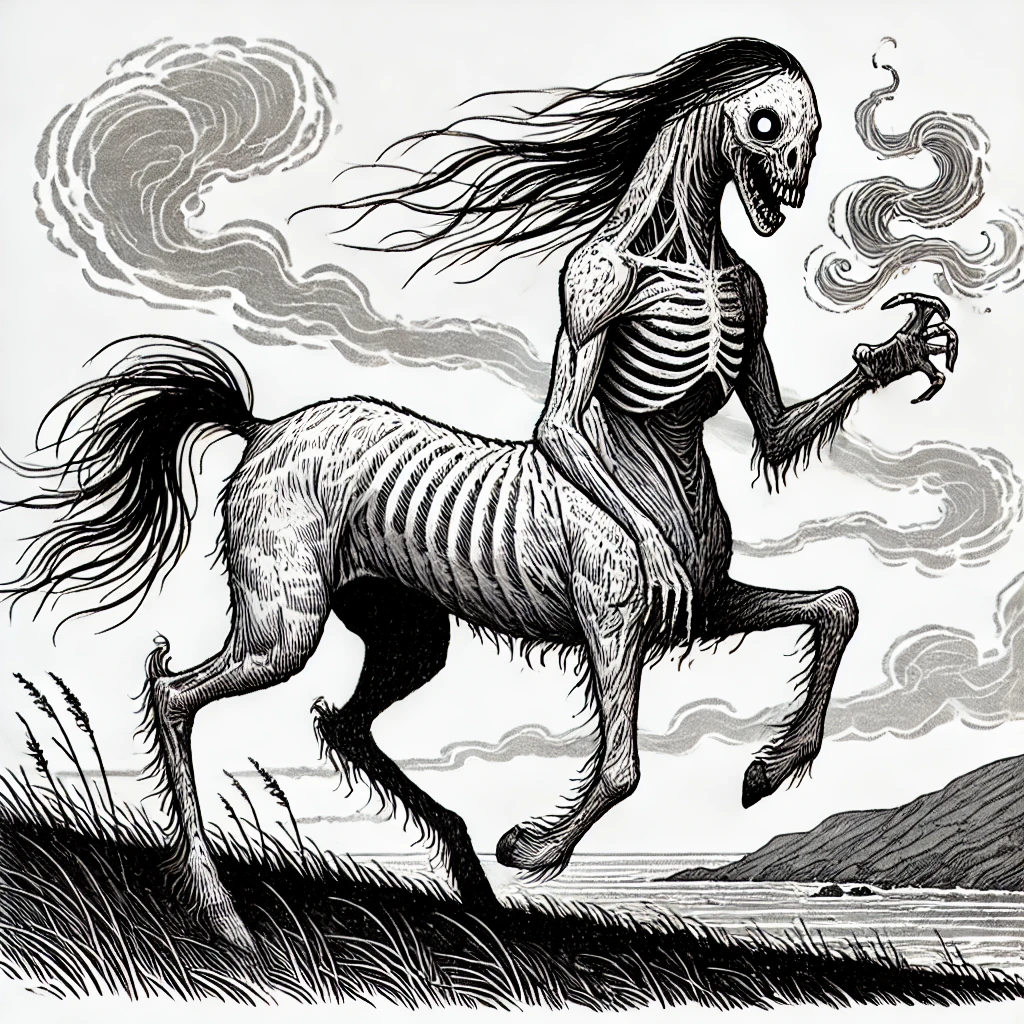

Mare

During my journey along the barren banks of the Lais River, towards the roots of Nasa Mountain, we came upon a particularly fearful village. As we spent the night at Mrs. Adolfsson's mansion, the maids and farmhands of Hällbacken told of a dark witch in Stormyran. Those who did not put horsehair in their hymnbook at night found themselves breathless and mare-ridden upon the rooster's crow. Maids in the village spoke with particular regret of Erik, the unmarried farmhand at Sten's Stud, who like the stallions in their stall had wasted away to skin and bones. Having put these stories into writing, my partner and I decided to head out into the marsh to seek the truth about the mare of the Lais River.

Carl Linnaeus, July 5th 1732

Mermaid

On the banks of Sörfolda fjord I saw items supposedly dating back to the dawn of mankind – crude axes and knives. They also showed me carvings near the waterline, claiming they had been made by the mermaid and her sea children. We headed out into the fjord on a fishing boat, and the fishermen called to her, throwing gifts of coins and gloves into the water. There was no sign of the mermaid.

Carl Linnaeus, July 13th, 1732

Myling

I asked my friend why it was that the dance hall in Nykarleby stood empty. She said that a mother had buried her unbaptized child beneath the floorboards to hide the identify of the father. During the dance, its spirit rose from under the floor and danced with its mother until blood was running down her legs and she died in the arms of her dead child. That is why people won't go near the dance hall without sharp steel or crosses. No one dances in Nykarleby.

Carl Linnaeus, September 22nd, 1732

Night Raven

We had wandered towards the shelter after the hymns of the midnight mass had gone quiet. The village priest of Bällinge claimed to have heard the horrifying shrieks beyond the snow-laden field to the east. But the mutilated bodies were not found until the sun finally dawned after the thick snowfall on Christmas Day, revealing the widow Egleus and her three children in a gruesome sludge of blood and night-black feathers. Landlord Fritjof Egleus, wretched and subdued, is said to have taken his own life to escape his harsh wife. Now, in the undead form of a wicked night bird, it seems he has had his revenge…

Carl Linnaeus, December 25th 1731

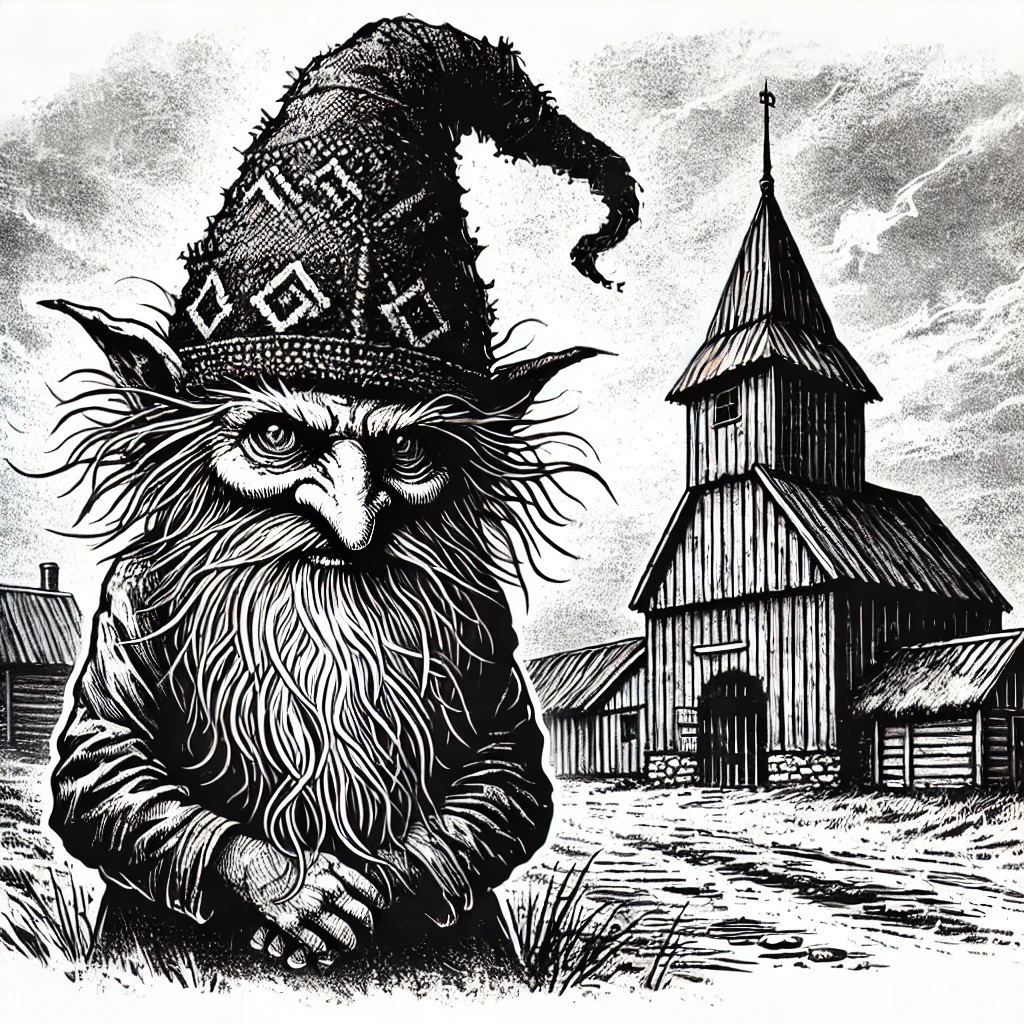

Nisse

The master of the farm in Nordmaling where we have been staying offered us buttermilk and flatbread. He said the cherry trees by the well rarely bear fruit, yet they cannot cut them down, as the farmstead nisse regards their berries as his property. The other day a farmhand pissed on the barn where the nisse has made its home. The following night, a calf was born whose legs, tail, and head had all been switched by the vengeful nisse. I asked the master to show me the animal. He obliged, and dug up a stillborn calf with a deformed body.

Carl Linnaeus, May 22nd, 1732

Nuckelavee

The tracks on the shore were neither horse, nor cow, nor sheep, yet the beast that made them was clearly a quadruped. For a full yard to either side of the creature’s path, the grass and heather were blackened and blighted. Its path made straight for the seaweed-burners’ camp, with but one deviation: instead of crossing the small stream that ran down from the loch, the tracks made a long circuit inland and around the spring-head. It was that which had saved the lives of those who saw the nuckelavee – though some would argue that their reason was not spared by the hideous sight.

William Stukeley, May 1726

Pixie

I have never in all my travels experienced such difficulty as I did on the road from Bodmin to St. Austell. A journey of no more than a dozen miles took all of the day and much of the night, so that it was near midnight when I arrived at my destination, cold, wet, and exhausted upon a cold, wet, and exhausted horse. Upon hearing my tale, the locals at the inn chuckled and exchanged knowing glances, assuring me that I had been “pixy-led” until the little people tired of their sport. Had I taken one of several well-known precautions, they said, I might have been spared the ordeal, and spent the afternoon and evening snug in the inn, as they had clearly done themselves.

William Stukeley, July 1719

Pooka

There were many in the village who could recount the tale of some encounter with the creature. One old dame, out gathering wood, had come across a pile of sticks that reared up at her when she tried to pick it up, hooting and mocking her in a human voice. A dairy maid told of chasing one cow ‘half across the farm’ only to discover, after she had given up the chase and walked near half an hour back, that the cow she sought was standing patiently by the milking-shed, and according to the farm hands had been there most of the morning. There were many such tales, all told with good humor, for the creature was never known to cause harm.

William Stukeley, September 1712

Redcap

The ruin of Dryholme Tower stands in a commanding position overlooking the coach road from Carlisle to Dumfries. Destroyed during the time of the Border Reivers, it is shrouded in legend and I was eager to survey the ruins. I quickly found, though that no one local could be induced to venture there at any price, for the tower was said to be haunted by those violent northern spirits known as red-caps, and it was held that to trespass there was death.

William Stukeley, July 1714

Revenant

As I write this, I am alone in the mountains. My companion is dead, and I am at my wits end. The two of us were heading for a goahti outside the foundry, and we were late. It was midnight, although the sun still shone upon the earth. My fellow traveler pushed rapidly ahead. I came across a plant previously unknown to me, picked it, and named it Andromeda. When I looked up, my companion was gone. I hurried after him, eventually entering the goahti. My companion lay dead before me, his face frozen in a dreadful grimace. Something emerged from the shadows. I screamed and ran. Now, here I am, the pen shaking in my hand. Where my pack is, I do not know.

Carl Linnaeus, July 20th, 1732

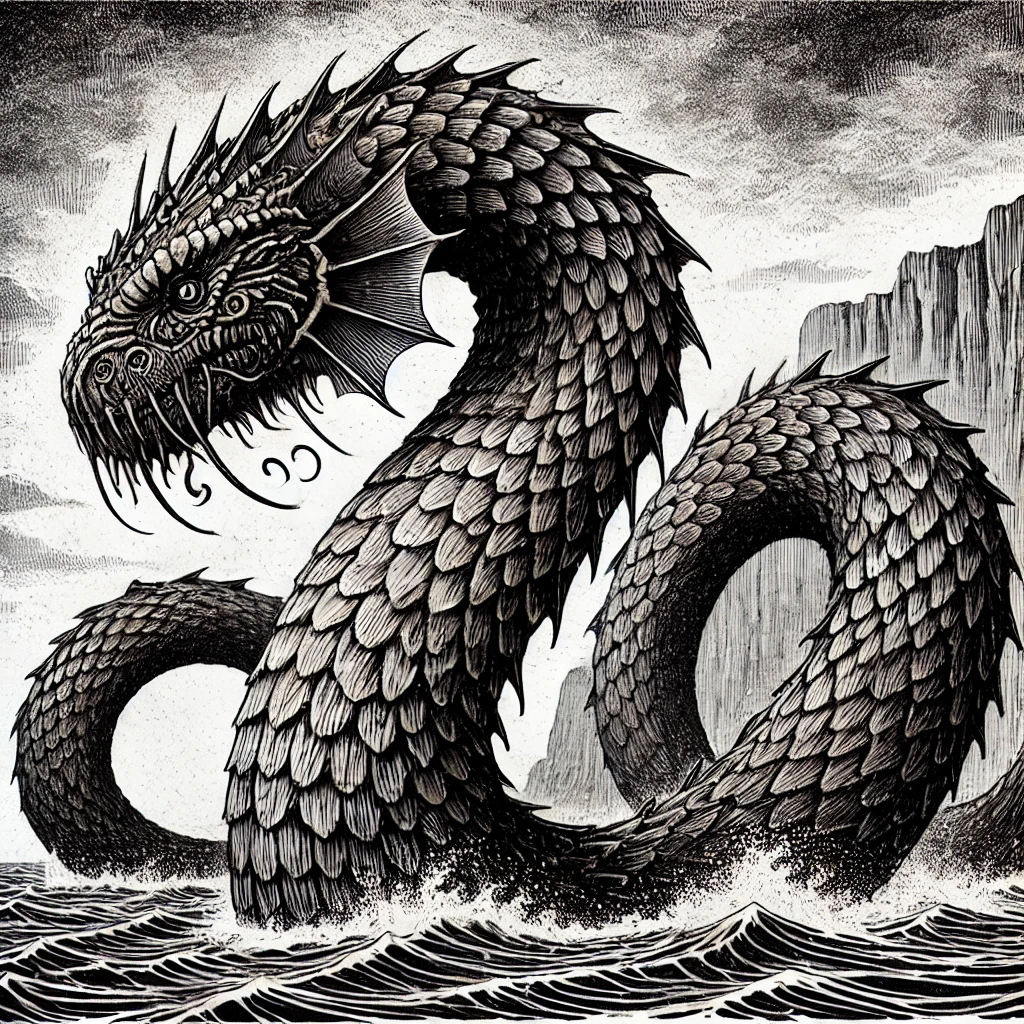

Sea Serpent

The stevedores at the port of Varberg spoke of many sailors meeting their end in the maw of the Kattegat Serpent. They say it dwells deep in the murky waters outside Læsø. I readily admit that these horror stories disturbed me, as we were set to board the wet deck of the schooner in the morning. But my journey to Amsterdam and the Tulip Kingdom could not wait. I can only hope that this sea serpent and its grisly deeds, like the fabled existence of the Great Lake Monster, are but stories from the thirsty throats of drunken travelers.

Carl Linnaeus, August 21st, 1735

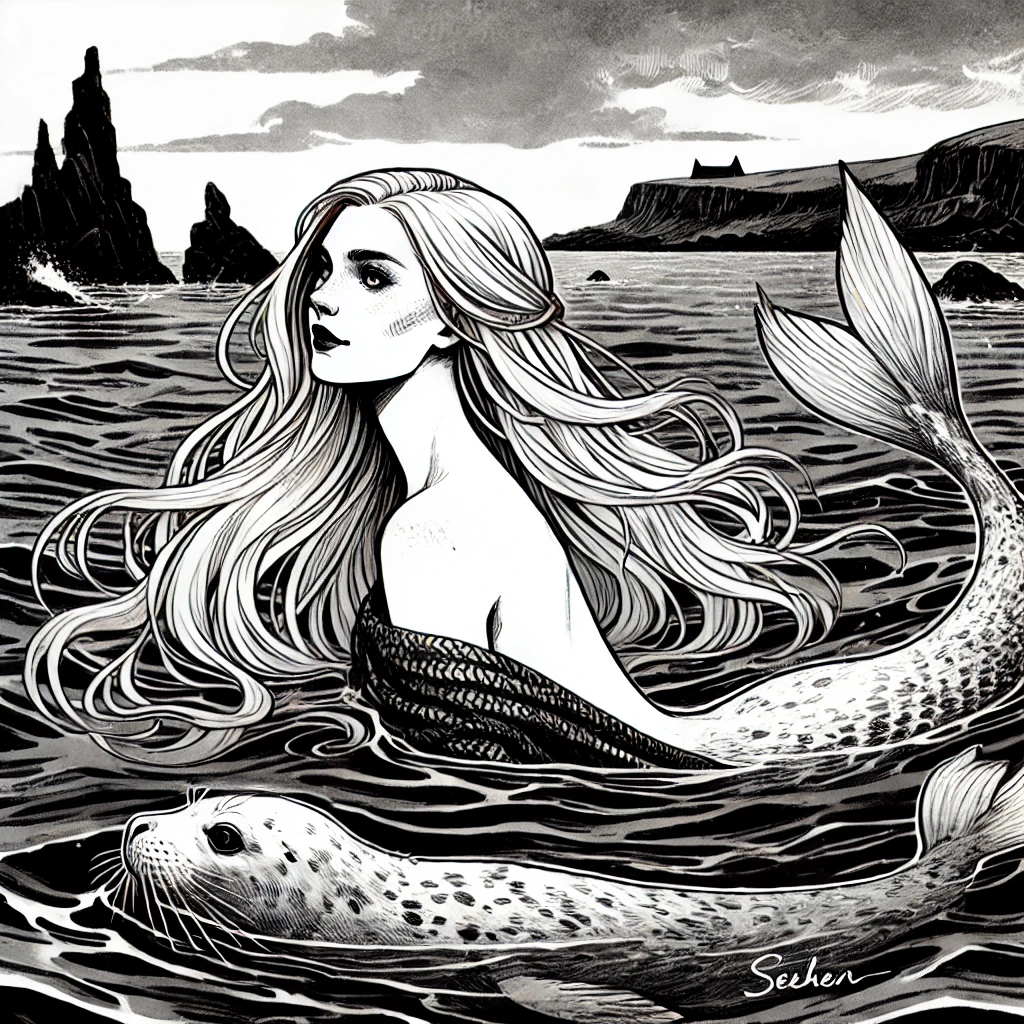

Selkie

One of my companions, seeing a fine, fat seal sunning itself on the strand, reached for his musket, but our guide stayed his hand. He explained that this seal was of a breed that the locals regard as supernatural, and that to harm one was to invite the worst possible luck.

William Stukeley, April 1726

Spertus

One of the hunters in Törfjorden showed me the dried deer bladders they would blow up, fill with liquor, and carry with them. He wanted to show me something else as well, which he said was the secret to his wealth and success. In his snuff box lay a small beetle of unknown species. It turned out to be alive, twisting and turning like a housewife on a feather bed, until the hunter gave it a good spit. Then it sprouted limbs with which I was not familiar. The man quickly put the lid back on. He would not sell me the creature, claiming it was worth more than all the gold of the mountain trolls.

Carl Linnaeus, July 12th, 1732

The Neck

I am sitting in a meadow, a cup of liquor in my hand, writing about a strange encounter. The people of Torneå complained about a pestilence killing the cattle as they were put out to pasture after the winter. This meadow is where they graze, not far from the river. I managed to identify the cause of their death. Vast quantities of Cicutaria aquatica grow in this place. I asked myself aloud why this plant was so abundant, and was answered by the sound of a flute. There was a man perched on a rock in the stream. He had the eyes of a goat, with black horns on his forehead. As I approached the man, he dove into the water. The tunes of his flute lingered in the air, and new sprouts of cicutaria sprung up all over the bank.

Carl Linnaeus, August 18th, 1732

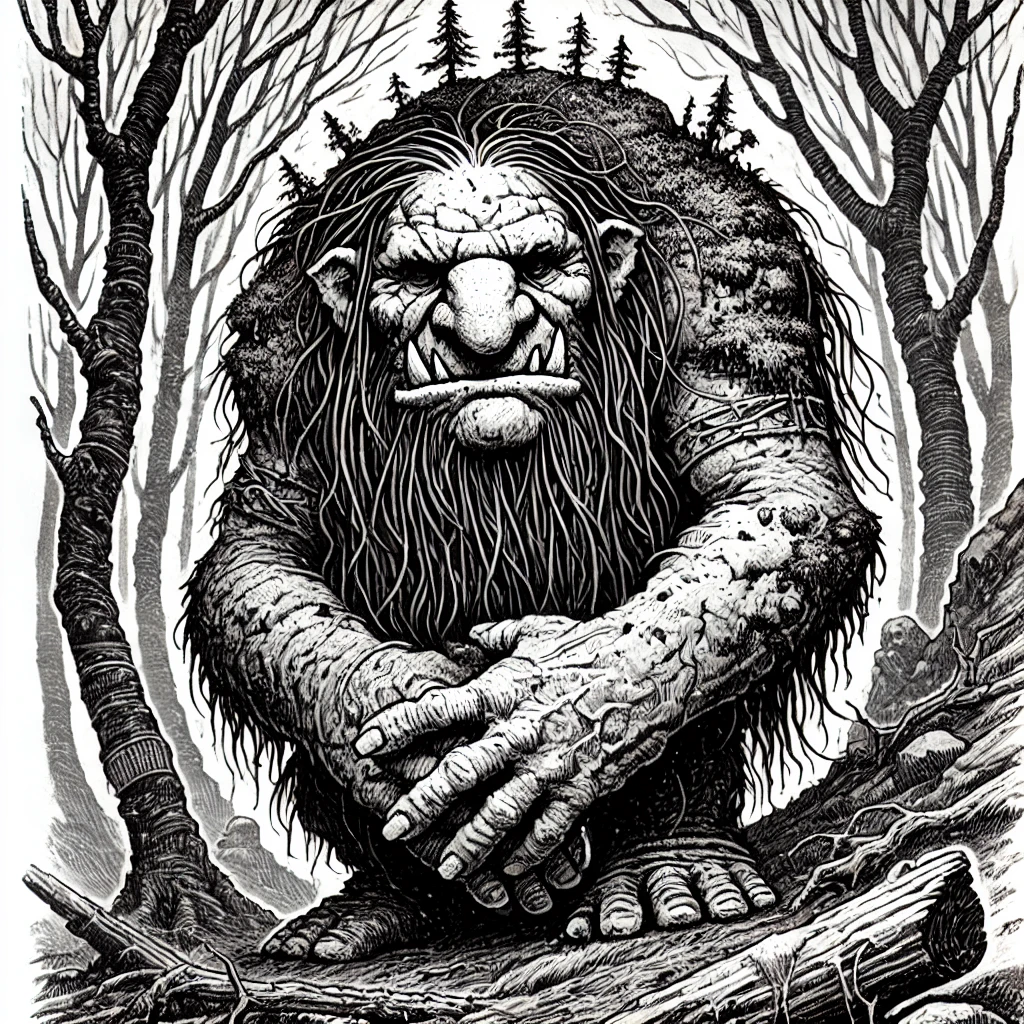

Troll

The strangest wedding I ever attended was here in Västerbotten. Inside the cabin, which was not very spacious, the tables were set not only for human guests but also the mountain trolls. Relatives of the groom brought dried meat and cheese. His mother and father had everyone drinking liquor from a jar, as the guests shook hands with each other. Many drinks were poured onto the ground, for the lady of the mountain. I was told the trolls had come to visit, invisible to human eyes. They were described as old men, bearded and gray. Apparently, their gifts were greater than those of the humans – not given during daytime, but placed around the sleeping bride and groom. I remember nothing else, either from the explanation or the wedding feast, as the schnapps flowed too freely. My head is throbbing, and I dread the light of day.

Carl Linnaeus, September 28th, 1732

Vaettir

This morning I left Reverend Solander's home in Piteå with my gift stuffed into my satchel. It was given to me by a vaesen no bigger than my forearm – a rat-like creature on two legs, who addressed me by name as I was trying to sleep. The creature begged me to move a water barrel that had been placed in the corridor outside the kitchen. I did what it asked, and found that the barrel was blocking a hole in the floor. A tiny figure popped out, smiling at me with its froggish face and tipping its hat. The next morning, I found my gift – a beautiful troll drum wrapped in birch leaves – upon my blanket.

Carl Linnaeus, June 17th, 1732

Werewolf

Officer Kock of the county police met us on the other side of Lake Virijaure. Before we had even climbed out of the boat, he came up to us through the thick fog, asking if we had seen a man dressed in wolf pelts with blood all over his body. Some stranger had run amok, slaughtering a maid and ripping out her heart. We knew nothing, and told him so. He asked that we keep our eyes open. That night we heard the howls of wolves, echoing through the woods and across the lake.

Carl Linnaeus, July 17th, 1732

Will-O'-Wisp

Bright green fir trees were everywhere as we left Umeå in the early hours of the morning. We made a short stop and found bog rosemary in full bloom. Soon the mist came creeping down from the mountain. My companion alerted me to a green light among the trees. I felt a sudden urge to follow its glow, which seemed to be moving deeper into the forest. The interpreter advised against it, and when I persisted, he grabbed me hard by the coat until the light had vanished. I grew angry, calling him a muck-eater and a smellfungus. Now I regret my words, wondering whether he somehow saved me from a tragic fate.

Carl Linnaeus, June 12th, 1732

Wood Wife

The woodds are composed of gray alders and birches with witches' brooms. (Nescio cur?) My horse collapsed several times during today's trip through Ångermanand. On one occasion I sustained a fracture. In the glow of the fire, I now write of a sight that took my mind off the pain. Encamped for the night, I emptied my bladder near a brook, when suddenly I saw three moose – one white, one brown, and one black – crowned with magnificent antlers. On the back of the white one rode a woman with antlers on her forehead. She was beautiful, with fair skin and green eyes. I could see from her look that we had her permission to visit the forest.

Carl Linnaeus, May 19th, 1732